In 4 articles for Entreprenante Afrique, the Café Lumière project in Madagascar is presented, and the results of different alternative evaluation methods carried out at an affordable cost are compared…

In 4 articles for Entreprenante Afrique, the Café Lumière project in Madagascar is presented, and the results of different alternative evaluation methods carried out at an affordable cost are compared to assess the existence of positive impacts of the project on development objectives. This fourth and final article explores the impacts on households by comparing changes in the variables of interest in treated and untreated localities, similar to the ‘localities’ part of our survey. Thanks to the sample size of households surveyed in each locality[1], we can assess the statistical significance of our conclusions and evaluate the risk of errors in our findings regarding the existence of an impact. We studied variables of interest that can logically be considered as measuring potential impacts of the project on households.

Access to electricity

On the sample of surveyed households, 18% are connected in May 2023to the mini-grid in localities equipped with a Café Lumière. The other forms of access to electricity were mainly individual fixed or mobile solar panels. The rate of access to electricity, defined as including all possible sources of electricity, was relatively similar between the two groups of localities in 2023, with 46% of households having access in localities with a Café Lumière compared to 43% in localities without one.

It is important to note that the rate of access to electricity was higher in localities that were subsequently equipped with Café Lumière (37%) compared to those without (27%), which is a significant difference. While there is no significant improvement in access to electricity from a quantitative point of view, there is a replacement of individual solar panels by connections to the mini-grid, which is considered a qualitative improvement. According to the Multi Level Framework (MTF) defined by the World Bank, the first type of access is considered level 1, while the connection to the mini-grid is level 2. This is due to two differences between the two types of access: higher available power and lower intermittency. Data on the use of electrical appliances corroborates this finding.

Use of electrical appliances

In order to analyse the use of electrical appliances, we calculate an index, which is the sum of the electrical appliances used by a household. The appliances taken into account are: cooker, refrigerator, fan, radio, television, video recorder, DVD player, computer, tablet, fixed telephone, and mobile phone. Thus, a household owing a fan and a radio would then have a score of 2, and a household possessing all of the mentioned items would have a score of 11.

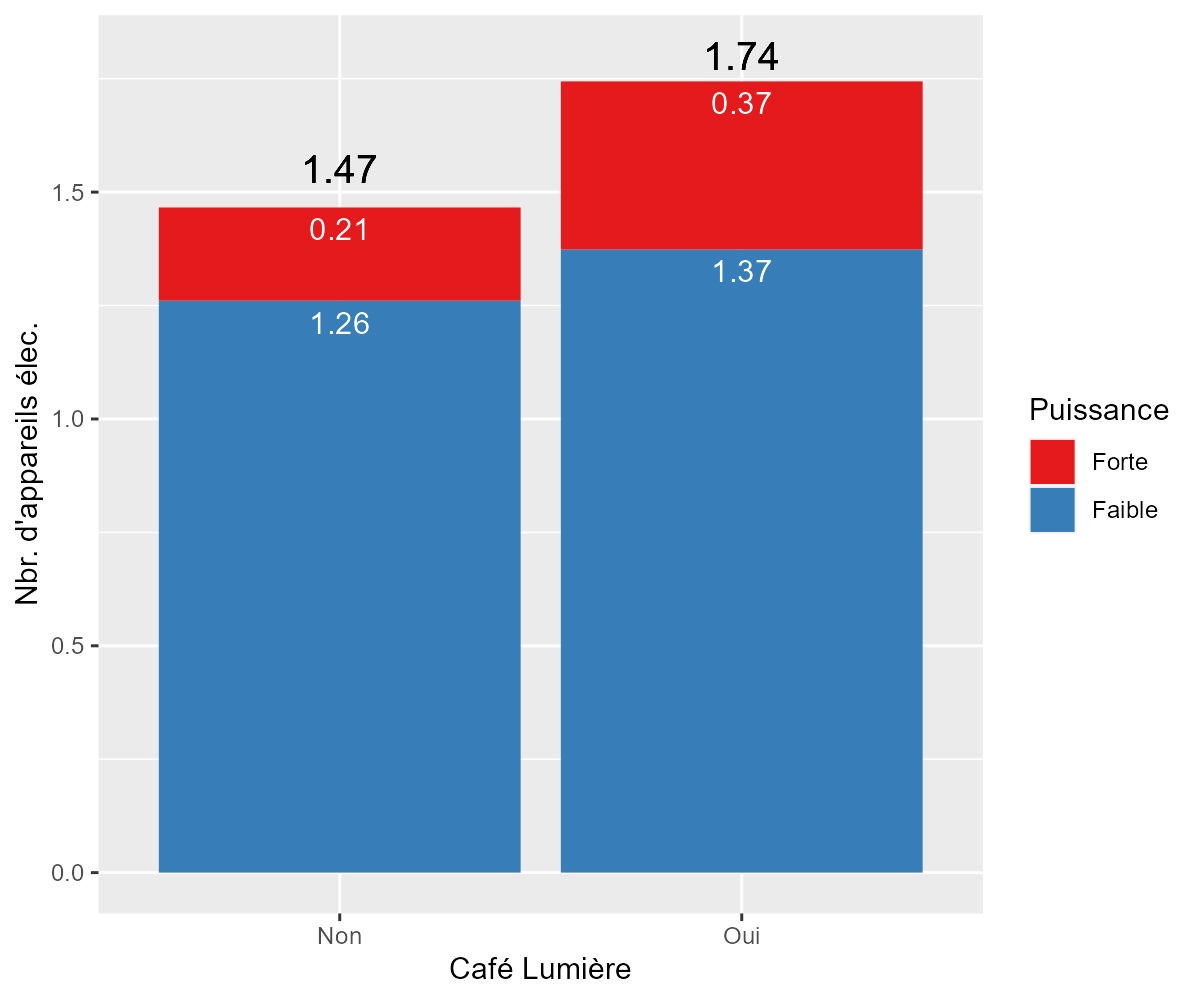

During the second wave of surveys, we observe that households living in localities with Café Lumière use more electrical appliances than those living in localities without Café Lumière. Households living in localities with Café Lumière have an average of 1.7 electrical appliances compared to only 1.5 in other localities. Although this difference may appear small, it is statistically significant at the 1% threshold.

The increase usage of electrical appliances in the treated localities is clearly due to the improved quality of access to electricity for the 18% of households now connected to the mini-grid.

To corroborate this conclusion, we construct a second index of electrical appliance usage, considering only appliances that require relatively high power to operate, typically unavailable when electricity access is at level 1 of the MTF. This index includes the following appliances: cooker, refrigerator, fan, television, video recorder, DVD player, and computer.

On this new index, we find a very significant positive impact of the Cafés Lumière. On average, households used only 0.20 high-power electrical appliances in 2023 in localities without a Café Lumière, whereas they used 0.37 in localities with Café Lumière (this figure even rises to 1.20 for households using the mini-grid, whereas there was no significant difference in 2017/2018).

Household wealth

To assess any potential impact of Café Lumière on household wealth levels, we construct a series of composite indices based on variables reflecting households’ material possessions. It is important to clarify that this index represents a stock of assets, rather than a flow such as the household’s monthly or annual income. We proceed with Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), which is a data analysis method that synthesises information from multiple qualitative variables into a few complementary axes. The axis containing the most information is generally considered representative of household wealth. The possessions of households used to calculate this composite wealth index take into account elements related to housing quality, such as materials used for the floor, walls, or roof, the number of rooms and floors, etc., as well as electrical appliances (see list above) and all belongings owned by the household, such as a bicycle, a moped, a car, a watch, etc. Each household is then assigned a score representing its level of wealth. This index has a mean of 0 and ranges from a minimum of -2.17 for the poorest household to a maximum of 5.22 for the wealthiest household.

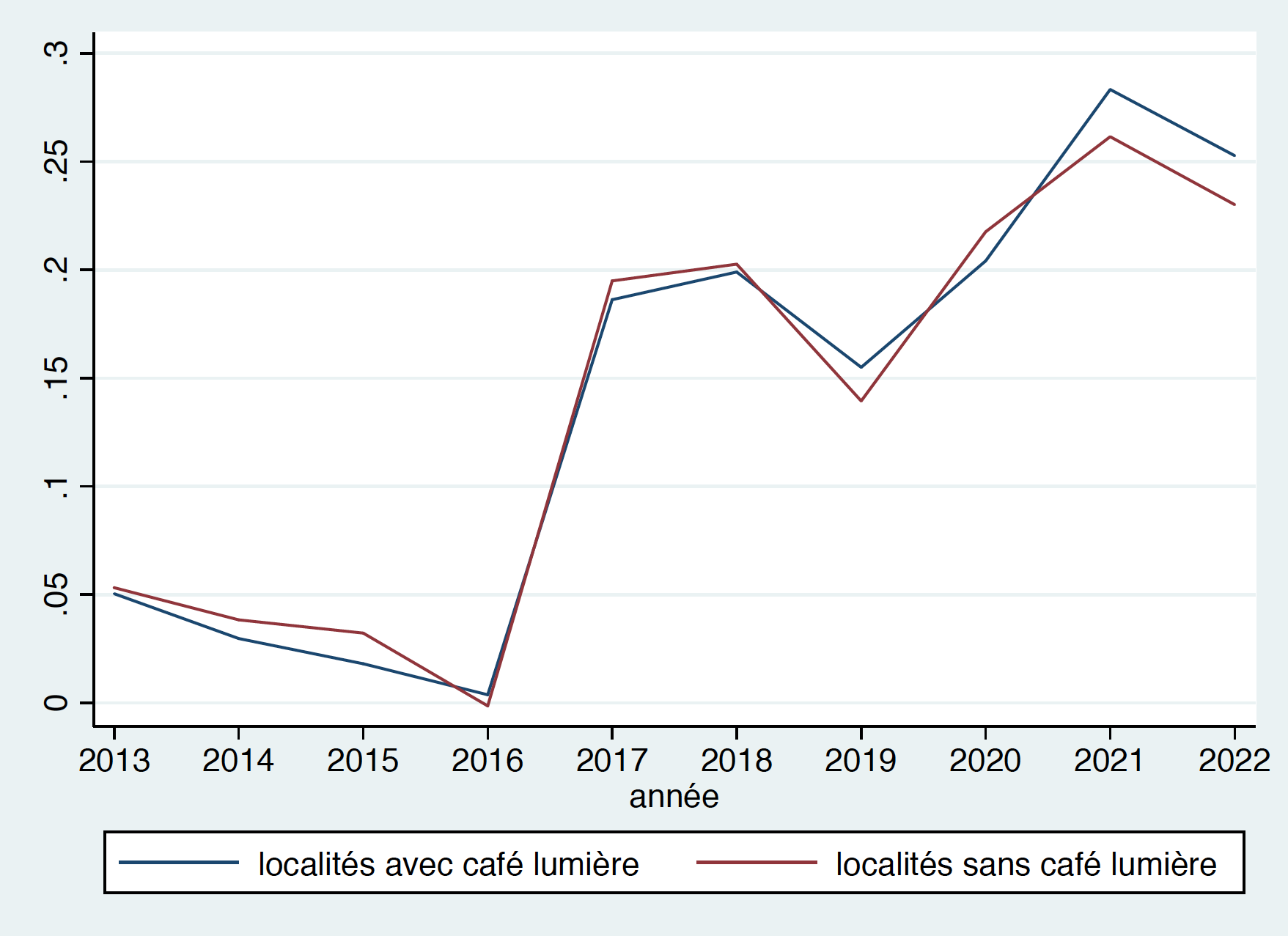

When we analyse the difference in scores in 2023 between localities equipped with Café Lumière and those without, we observe that the average wealth index of households living in localities with Café Lumière is higher, albeit not quite significantly. As illustrated in Figure 1, the average wealth index for localities with Café Lumière is 0.19 compared to only 0.03 for localities without Café Lumière. The absence of disparity in 2017/2018 strengthens the robustness of this conclusion. It is noteworthy that when we calculate the wealth index without taking into account ownership of electrical appliances, what we could call a “non-electricity wealth index”, we find no impact of Café Lumière. This leads us to conclude that while Café Lumière may have had a positive impact on electricity access and its usage by households, this improvement in their material living conditions has not yet spread more widely.

Socio-economic data

Beyond the objectives of improving the overall energy and economic situation in the treated localities, the main objective of the Café Lumière project is to contribute to socio-economic progress. Regarding economic poverty, we observe a slight improvement in the distribution of the wealth index benefiting the poorest 20%, but this cannot be directly attributed to the introduction of Café Lumière.

Looking at access to health and education, which are the areas most often studied in similar evaluations, we find some evidence of impact in the first area, but not in the second. This is consistent with the localities section of our survey, which showed many health centres connected to the mini-grids, but proportionately fewer schools.

Finally, we examined the project’s effects on the insecurity associated with theft of livestock, crops, or other goods experienced by households in rural regions of Madagascar. It is often argued that the introduction of public lighting at night may help improve this situation, but this is not clearly proven at this stage.

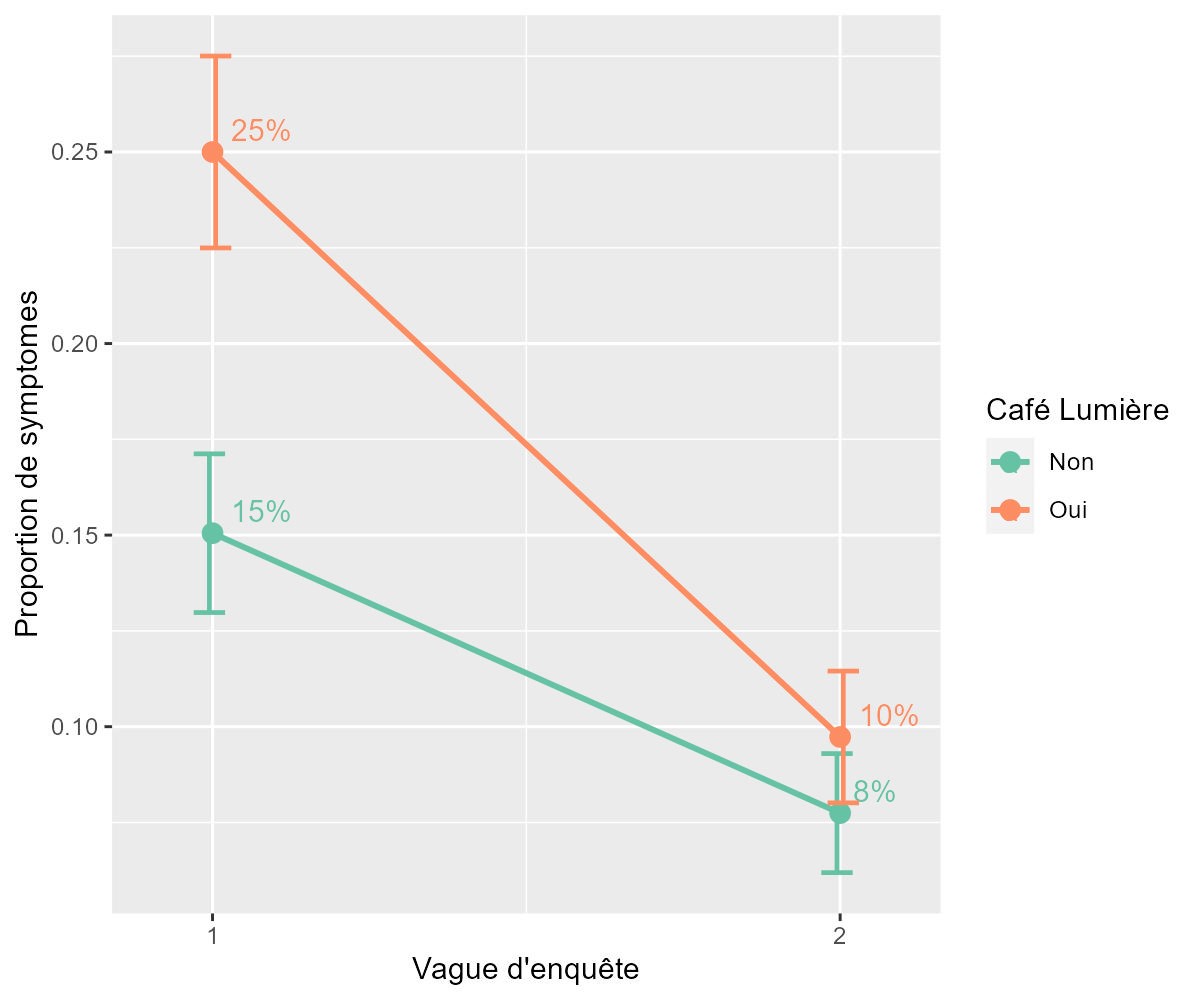

In terms of health issues, if we compare reports of symptoms such as respiratory problems (cough/cold, etc.), diarrhoea, fever, headache and eye problems or burns, we find no significant difference between the two groups of localities in 2023. However, it is interesting to note that during the first wave of the survey, i.e., before the installation of the Cafés Lumière, symptoms were much more prevalent in the localities that received the Cafés Lumière, and these localities experienced a significant decrease in symptoms prevalence between the two waves, which could be interpreted as a consequence of the Cafés Lumière project.

Focus on childbirth: we observe that childbirths occurring in a well-lit environment due to electricity have become almost routine in localities with a Café Lumière. Indeed, for women living in a locality with Café Lumière, 78% of them give birth in facilities with electric lighting compared to only 40% in other localities. This difference in average is statistically highly significant.

Conclusions

This fourth and final stage of our series of articles on the evaluation to date of the impacts of the Café Lumière project in Madagascar has allowed us to study the benefits received by the population of the concerned localities in terms of access to electricity and livings standard, as well as its impacts on socio-economic development. Before the implementation of the project, the studied localities were not characterised by absolute energy poverty, which can be defined by the absence of access to any source of electricity. On average, in 2017-2018, one-third of households already had access to electricity through standalone solar panels.

The most visible energy impact of the project on households is that 18% of households in equipped localities now benefit from a connection to the mini-grid. For these households, this energy impact is significant as it results in the use of more numerous and higher-powered electrical appliances. In our previous blog article, we had also shown that some subscribed households used their subscription for both their own consumer needs and for income-generating activities.

We have observed that in the equipped localities, the wealth index of households has increased, but only when taking into account the ownership of electrical appliances. Therefore, the enrichment of households through the arrival of the mini-grid does not seem to have created economic transformation beyond the acquisition by connected households of some electrical appliances requiring the transition to higher power and lower intermittency provided by the mini-grid. Efforts still need to be made for the poorest households, as even though they benefit from improved public services and shop services, they cannot yet trigger genuine economic development. This observation echoes the fact that we had shown in our previous article that, so far, the impact on income-generating activities had been limited to the electrification of their production tools by the mini-grid.

In the social spheres, the arrival of mini-grids has had positive impacts on health. The situation has particularly improved due to the connection of primary health centres (csb2) to mini-grids. The improvement in public health has also benefited from synergy with other national and international programmes in collaboration with the World Bank and UNICEF, notably for vaccination campaigns.

The impacts observed so far appear to be limited, but this observation needs to be put into perspective by the fact that we are currently only seeing short-term impacts. Thus, if all equipped localities were to achieve the same results as the most successful locality in terms of household connections, Talata Dondona (36%), we would double the number of household connections. Furthermore, economic transformations that can be stimulated by purely energy-related impacts necessarily take a long time to materialise. The same applies to socio-economic progress, which may require complementary public policies, as in the case of healthcare.

[1] 599 households were interviewed during the first wave (2017/2018), and 595 during the second wave (2023). 133 households from the first wave were not found during the second. They were replaced by 129 new households. In total, 466 households were surveyed during both waves.

![]() Further reading in the same serie of articles on “Measuring the Impact of Decentralised Electrification Projects”: Cafés Lumière in Madagascar (1/4), Using Remote Sensing: Initial Results on the Impact of Cafés Lumière (2/4), Characterisation of the Impacts of Decentralised Electrification Projects on Access to Electricity Using Locality Data (3/4).

Further reading in the same serie of articles on “Measuring the Impact of Decentralised Electrification Projects”: Cafés Lumière in Madagascar (1/4), Using Remote Sensing: Initial Results on the Impact of Cafés Lumière (2/4), Characterisation of the Impacts of Decentralised Electrification Projects on Access to Electricity Using Locality Data (3/4).