In 2019, Algeria has been at the forefront of African political life, with the resignation of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika in April. The economy is currently suffering, not so much from…

In 2019, Algeria has been at the forefront of African political life, with the resignation of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika in April. The economy is currently suffering, not so much from its growth rate, price, and cost competitiveness, as from its inability to diversify and create the hundreds of thousands of jobs needed each year for the annual cohort of young people who enter the labor market.

A lack of public support for entrepreneurship

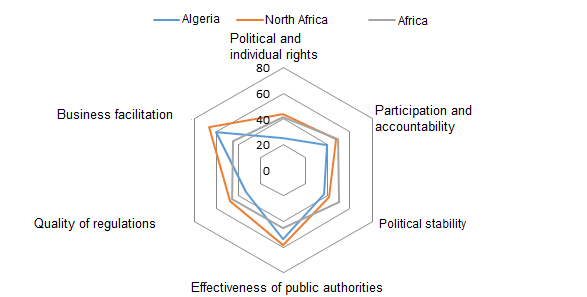

When we compare its political and economic governance to other countries, Algeria is lagging behind the North African average, and in some aspects, behind the African continental average.

The Algerian context of individual freedoms has not allowed citizens to engage in politics fully. In this background, the accountability of public decision-makers has been structurally low, although raw material resource rents have helped to buy some “social peace” through subsidies for household consumption (Le Billon, 2003).

The last four presidential terms (1999-2014) have permitted a return to civil peace. The regime has gradually opened up to more cooperation with the private sector, but has never really abolished cronyism. Consultation frameworks have fostered actors close to, and respectful of, the authorities. This networking spirit has produced significant shortcomings in the transparency of public actions and the establishment of effective competition mechanisms. With an inexorable rise in social discontent, the government’s responses focus more on the short term than on the implementation of a strategic vision with long-term measures compatible with the requirements of globalization and job creation.

The continuation of half-measures has helped to alter the desire for reforms to protect the economy from the vulnerabilities associated with the downturn in the commodity “super cycle”. Short-term rent management and cronyism have hindered the initiative of local entrepreneurship and have not taken into account long-term perspectives in a context of high corruption.

So far, both the stimulation of business creation and the opening of tenders to agents without connections to the “political clan” have remained timid. Current events will determine to what extent the organization of political, economic, and social life will lead to public order and civil peace. The success of the change of President will determine Algeria’s ability to project itself into the more integrated sub-regional space which is expected to develop with the prospect of ECOWAS enlargement and the establishment of the African continental free trade area.

Prices and costs in line with competitiveness

The FERDI Sustainable Competitiveness Observatory (SCO) has Algeria in first place to for price competitiveness, both for North Africa and for the whole continent. This position, which could not be more flattering, cannot fail to amaze. It suggests that diversification has not suffered from the “Dutch disease” caused by oil and gas rents, which generally drives up costs to the point of crowding out the production of non-primary tradable goods (Djoufelkit 2008).

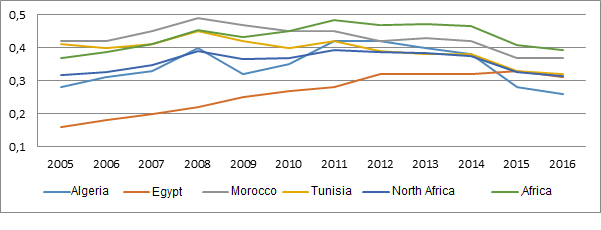

The purchasing power conversion factor against the dollar estimates that the cost of the basket of goods in 2016 was only 25% of the price in the United States, 40% of the African average and 30% of the average for North African countries (Graph 1). In Algeria, the level of wages is also relatively low. The wages of a cashier in a supermarket are much lower, at the current exchange rate than in other North African countries, and are not very far from the African average; but Algeria is an upper-middle-income country. However, a more detailed analysis of prices leads to nuanced conclusions.

Graph 1: Evolution of the Algerian Dinar conversion factor

* The conversion factor for purchasing power parity used here is the number of units of national currency required to purchase the same amount of goods and services in the domestic market that a US dollar would buy in the United States.

The first reason for the nuanced price competitiveness is the consequence of an interventionist tradition which contributes to define prices that do not necessarily reflect the reality of market prices, and to a framework of commercial margins that is still prevalent. In December 2017, a problem arose in concrete terms for bread. Hundreds of bakeries had taken the initiative to defy public regulations by raising the price of a baguette to 15 dinars. At that time the official price was 8.5 dinars, unchanged since 1996, with a typical price of 10 dinars in Algiers. According to the federation of bakers, which is not recognized by the Government, the price regulation, which no longer covered production costs, could force many bakeries to close. The difficulty is to make economic logic and social logic compatible. As in most developing countries, the price of bread is a sensitive issue, because it is an essential part of household food consumption. For a population of more than 41 million inhabitants in 2017, 70 million baguettes would be sold every day!

Interventionism in price may correspond to instant consumer protection, but may cause problems in the longer term. It impoverishes the competitive market and leads to the emergence of cheating on product quality. Beyond bread, public preference for regulation can, therefore, lead to distortions in the allocation of resources within the economy. It leads to uncertainties about the profitability of companies with implications that are poorly measured for the long-term well-being of the community

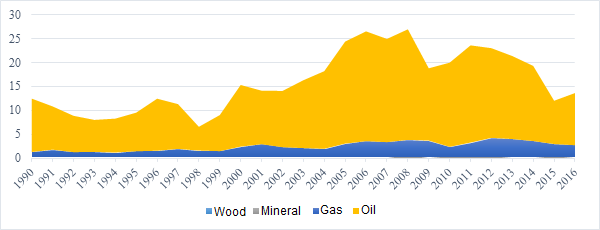

The second reason for the nuanced price competitiveness, stems from public subsidies. With prices maintained below the economic cost, a subsidy can compensate the producer for the loss of income. For this economic logic to hold permanently, it is necessary to assume that these subsidies are sustainable. To validate this assumption information about the cost of oil and gas production is strategic. However, little is known about it. For Algeria, the break-even point per barrel of oil would be a price of between $20 and $40. Given the importance of oil and gas in the country’s economy, we can see the influence of these rents on GDP and their contribution to the financing of the State budget (upto 60% of revenue).

Graph 2: The percentage of rents in Algeria’s GDP (1990-2016)

Consumer subsidies and transfers to the economy have become the Achilles’ heel of Algerian public finances. Their share of GDP has tended to increase since the late 1990s, from 4% to around 12% in 2012, while in 2012 oil prices had not yet started to decline. The consumer products concerned are numerous. In the fiscal year 2015, IMF staff estimated that subsidies cost about 14% of GDP and were equivalent to twice the combined annual budgets of the Ministries of Health and Education. According to the most recent figures from the Ministry of Finance, about 10% of direct subsidies are covered by the State budget. 18% are implicit subsidies, such as tax advantages granted to companies for their investments, which are more difficult to assess,. The role of these subsidies is essential. Probably, the new Algerian government team will quickly be faced with the daunting dilemma of choosing between companies and consumers, between the short term and the long term in an approach that has to be both coherent and compatible with political feasibility.

References

Le Billon, P. (2003). Buying peace or fuelling war: the role of corruption in armed conflicts. Journal of International Development, 15(4), 413-426. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.993

Djoufelkit. H, (2008), « Rente, développement du secteur productif et croissance en Algérie », AFD, Document de travail, n°64, Paris. https://www.afd.fr/

Observatoire de la compétitivité durable : https://competitivite.ferdi.fr/