Typically, current assessments of decentralised electrification projects struggle to establish their tangible impact. Achieving this would necessitate expensive and time-intensive efforts, because it would demand extensive data not only from…

Typically, current assessments of decentralised electrification projects struggle to establish their tangible impact. Achieving this would necessitate expensive and time-intensive efforts, because it would demand extensive data not only from the equipped localities but also from control localities. Nonetheless, substantiating the presence of an impact is crucial to assist public decision-makers, both at the national and international levels, in expanding the adoption of these solutions.

In a series of four articles for “Entreprenante Afrique,” we introduce the Cafés Lumière mini-grids project in Madagascar and compare the outcomes of various affordable evaluation methods applied to these projects. These methods aim to assess the project’s positive effects on development objectives. In this second of four articles, we explore the feasibility of evaluating impacts through the use of remote sensing data, which is generally a low cost approach.

The contribution of remote sensing to impact analysis

Remote sensing uses high-resolution satellite imagery that covers nearly the entire globe, offering near real-time accessibility at a low cost. This technology can effectively capture various measurable terrestrial phenomena relevant for the study of human activities. For the assessment of electrification projects’ impacts, satellite imagery measurements of night-time luminosity can be employed, once sufficient experience has been gained in interpreting this data. It has been consistently demonstrated that an increase in night-time luminosity correlates well with the increase in electrification over time, even at fine levels of granularity (see Berthélemy, 2022, in The Conversation). It has even been argued that rise in night-time luminosity reflects growth in economic activity (Hu and Yao, 2022).

Nonetheless, critics of this new approach, which relies on observations of natural phenomena partially linked to the outcomes of human activities, raise concerns about potential assessment bias. In our context, night-time luminosity specifically measures the light generated at night, primarily from lighting sources, especially public lighting. It does not have a direct connection with total electricity consumption, of which it typically represents a minor portion, and even less so with its impacts on socio-economic development. While public lighting can influence safety, and consequently economic activity, it can only capture a fraction of the consequences of electrification on human activities.

Application: the Cafés Lumière Mini-grids have a Significant Impact from 2021 onwards

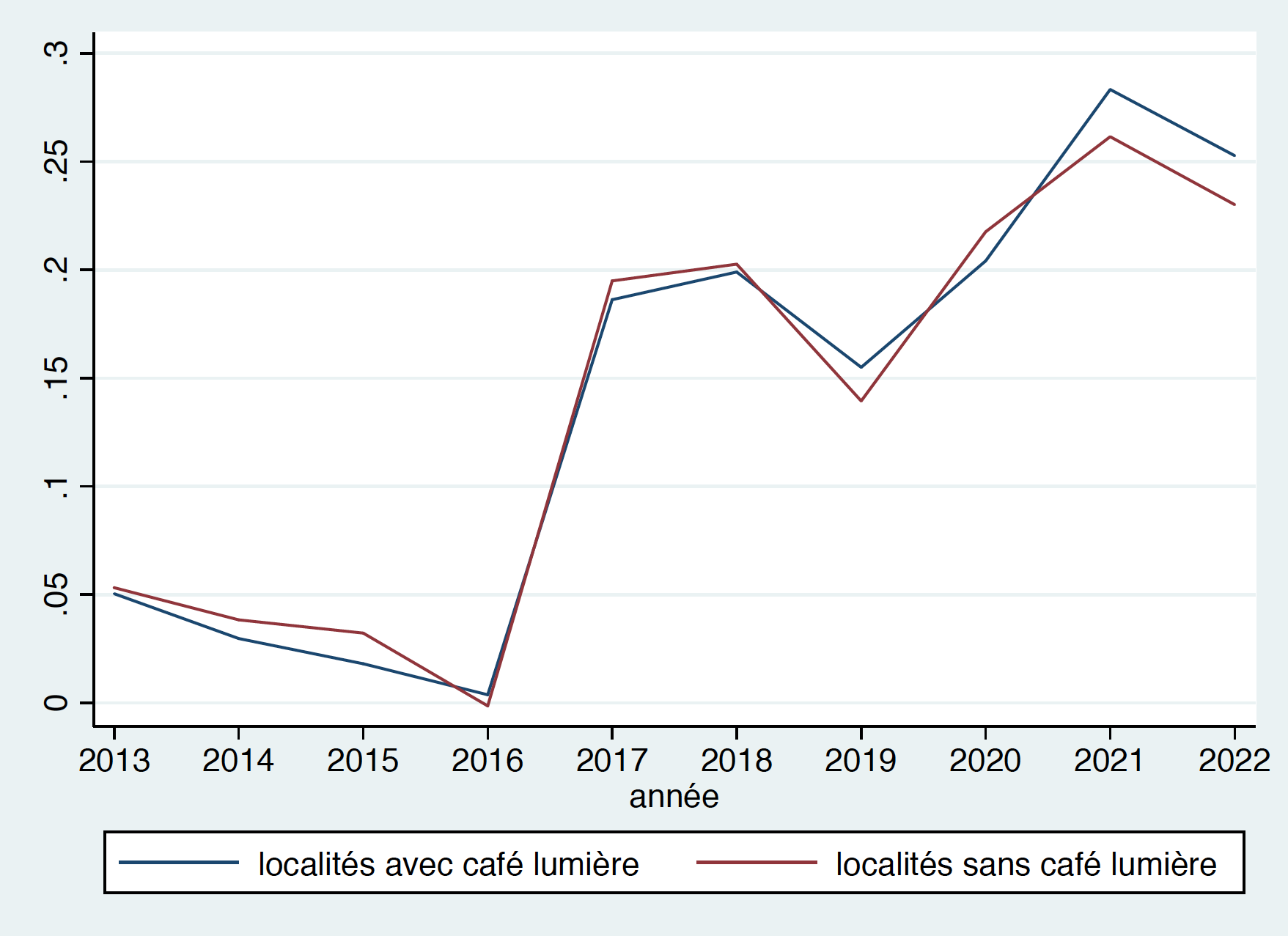

Night-time luminosity can serve as a real-time indicator for detecting the effects of electrification. To illustrate this, we have calculated the average annual night-time luminosity for the 6 equipped localities and compared it to that of 6 similar non-equipped localities, which were randomly selected by Electriciens sans frontières to create a control group. The data was analysed taking into consideration the following constraints :

- The different localities were not equipped at the same time ;

- The Cafés Lumière were progressively set up, with priority given to installing the shop before commissioning the mini-grid. Since the shop has little effect on light emission, the effects of Café Lumière can be initially evaluated by examining the influence of the mini-grid ;

- In 2 localities, Ambatonikolahy and Talata Dondona. public lighting operates during specific hours when the satellite passes overhead (between 12pm and 2am in our case). Other localities prefer to have public lighting from 9pm to midnight and from 5am to 6am.

Figure 1: Assessment of night-time brightness (annual averages 2013-2022) in both equipped and non-equipped localities (radiance measured in w/cm2_sr)

Figure 1 shows a similar trend in the average night-time brightness for both the 6 equipped villages and the 6 control villages up to 2020. However, the equipped group exhibit more brightness in 2021 and 2022. This difference is approximately 10% compared to previous data, which, though modest given the initially low level, is statistically significant. Our findings from Figure 1 are corroborated by a more formally rigorous statistical test that utilizes monthly data for each locality, while also controlling for the seasonal effects and fixed effects associated with each treated or untreated locality. The deployment of the mini-grid leads to an increase in night-time luminosity comparable to that depicted in Figure 1, and this increase is statistically significant.

Concerns about potential bias arising from the presence of street lighting are only potentially justified in the case of 2 out of the 6 localities (Ambatonikolahy and Talata Dondona). In principle, these concerns can be examined by considering that street lighting is often installed subsequent to the mini-grid becoming operational. These fears are not borne out. In fact, when we attempt to account for both the presence of the mini-grid and street lighting simultaneously, the latter shows no significant effect.

This does not imply that public lighting has no effect; rather, it suggests that we are unable to provide demonstrable evidence of its effect. This limitation may be attributed to the statistical power of the test, given the small number of observations with the presence of public lighting.

In the third article, we will employ more precise data, notably on monthly electricity consumption categorized by usage, which will enable us to assess the contribution of public lighting to the increase in night-time luminosity.

![]() Further reading in the same serie of articles on “Measuring the Impact of Decentralised Electrification Projects”: Cafés Lumière in Madagascar (1/4), Characterisation of the Impacts of Decentralised Electrification Projects on Access to Electricity Using Locality Data (3/4), Characterisation of the Impacts of Decentralised Electrification Projects on Access to Electricity Using Household Data (4/4).

Further reading in the same serie of articles on “Measuring the Impact of Decentralised Electrification Projects”: Cafés Lumière in Madagascar (1/4), Characterisation of the Impacts of Decentralised Electrification Projects on Access to Electricity Using Locality Data (3/4), Characterisation of the Impacts of Decentralised Electrification Projects on Access to Electricity Using Household Data (4/4).